Line-of-sight propagation

Line-of-sight propagation refers to electro-magnetic radiation or acoustic wave propagation. Electromagnetic transmission includes light emissions traveling in a straight line. The rays or waves may be diffracted, refracted, reflected, or absorbed by atmosphere and obstructions with material and generally cannot travel over the horizon or behind obstacles.

At low frequencies (below approximately 2 MHz or so) radio signals travel as ground waves, which follow the Earth's curvature due to diffraction with the layers of atmosphere. This enables AM radio signals in low-noise environments to be received well after the transmitting antenna has dropped below the horizon. Additionally, frequencies between approximately 1 and 30 MHz, can be reflected by the F1/F2 Layer, thus giving radio transmissions in this range a potentially global reach (see shortwave radio), again along multiply deflected straight lines. The effects of multiple diffraction or reflection lead to macroscopically "quasi-curved paths".

However, at higher frequencies and in lower levels of the atmosphere, neither of these effects are significant. Thus any obstruction between the transmitting antenna and the receiving antenna will block the signal, just like the light that the eye may sense. Therefore, since the ability to visually see a transmitting antenna (disregarding the limitations of the eye's resolution) roughly corresponds to the ability to receive a radio signal from it, the propagation characteristic of high-frequency radio is called "line-of-sight". The farthest possible point of propagation is referred to as the "radio horizon".

In practice, the propagation characteristics of these radio waves vary substantially depending on the exact frequency and the strength of the transmitted signal (a function of both the transmitter and the antenna characteristics). Broadcast FM radio, at comparatively low frequencies of around 100 MHz, are less affected by the presence of buildings and forests.

Contents |

Radio horizon

The radio horizon is the locus of points at which direct rays from an antenna are tangential to the surface of the Earth. If the Earth were a perfect sphere and there were no atmosphere, the radio horizon would be a circle.

The radio horizon of the transmitting and receiving antennas can be added together to increase the effective communication range. Antenna heights above 1,000,000 feet (189 miles; 305 kilometres) will cover the entire hemisphere and not increase the radio horizon.

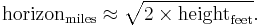

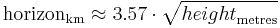

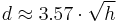

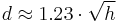

Radio wave propagation is affected by atmospheric conditions, ionospheric absorption, and the presence of obstructions, for example mountains or trees. Simple formulas that include the effect of the atmosphere give the range as:

The simple formulas give a best-case approximation of the maximum propagation distance but are not sufficient to estimate the quality of service at any location.

Earth bulge and atmosphere effect

Earth bulge is a term used in telecommunications. It refers to the circular segment of earth profile which blocks off long distance communications. Since the geometric line of sight passes at varying heights over the Earth, the propagating radio wave encounters slightly different propagation conditions over the path. The usual effect of the declining pressure of the atmosphere with height is to bend radio waves down toward the surface of the Earth, effectively increasing the Earth's radius, and the distance to the radio horizon, by a factor around 4/3. [1] This k-factor can change from its average value depending on weather.

Geometric distance to horizon

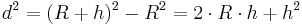

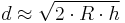

Assuming a perfect sphere with no terrain irregularity, the distance to horizon from a high altitude transmitter (i.e., line of sight) can readily be calculated.

Let R be the radius of Earth and h be the altitude of a telecommunication station. Line of sight distance d of this station is given by the Pythagorean theorem;

Since the altitude of the station is much less than the radius of the Earth,

If the height is given in metres, and distance in kilometres, [2]

If the height is given in feet, and the distance in miles,

The actual service range

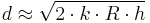

The above analysis doesn’t take the effect of atmosphere on the propagation path of the RF signals into consideration. In fact, the RF signals don’t propagate in straight lines. Because of the refractive effects of atmospheric layers, the propagation paths are somewhat curved. Thus, the maximum service range of the station, is not equal to the line of sight (geometric) distance. Usually a factor k is used in the equation above

k > 1 means geometrically reduced bulge and a longer service range. On the other hand, k < 1 means a shorter service range.

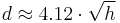

Under normal weather conditions k is usually chosen [3] to be 4/3. That means that, the maximum service range increases by % 15

for h in m. and d in km.

for h in ft. and d in miles ;

But in stormy weather, k may decrease to cause fading in transmission. (In extreme cases k can be less than 1.) That is equivalent to a hypothetical decrease in Earth radius and an increase of Earth bulge.[4]

Example

In normal weather conditions, the service range of a station at an altitude of 1500 m. with respect to receivers at sea level can be found as,

Line-of-sight propagation as a prerequisite for radio distance measurements

Travel time of radio waves between transmitters and receivers can be measured disregarding the type of propagation. But, generally, travel time only then represents the distance between transmitter and receiver, when line of sight propagation is the basis for the measurement. This applies as well to RADAR, to Real Time Locating and to LIDAR.

This rules: Travel time measurements for determining the distance between pairs of transmitters and receivers generally require line of sight propagation for proper results. Whereas the desire to have just any type of propagation to enable communication may suffice, this does never coincide with the requirement to have strictly line of sight at least temporarily as the means to obtain properly measured distances. However, the travel time measurement may be always biased by multi-path propagation including line of sight propagation as well as non line of sight propagation in any random share. A qualified system for measuring the distance between transmitters and receivers must take this phenomenon into account. Thus filtering signals traveling along various paths makes the approach either operationally sound or just tediously irritating.

Impairments to line-of-sight propagation

Low-powered microwave transmitters can be foiled by tree branches, or even heavy rain or snow.

If a direct visual fix cannot be taken, it is important to take into account the curvature of the Earth when calculating line-of-sight from maps.

The presence of objects not in the direct visual line of sight can interfere with radio transmission. This is caused by diffraction effects: for the best propagation, a volume known as the first Fresnel zone should be kept free of obstructions.

Reflected radiation from the ground plane also acts to cancel out the direct signal. This effect, combined with the free-space r−2 propagation loss to a r−4 propagation loss. This effect can be reduced by raising either or both antennas further from the ground: the reduction in loss achieved is known as height gain.

Mobile telephones

Although the frequencies used by mobile phones (cell phones) are in the line-of-sight range, they still function in cities. This is made possible by a combination of the following effects:

- r−4 propagation over the rooftop landscape

- diffraction into the "street canyon" below

- multipath reflection along the street

- diffraction through windows, and attenuated passage through walls, into the building

- reflection, diffraction, and attenuated passage through internal walls, floors and ceilings within the building

The combination of all these effects makes the mobile phone propagation environment highly complex, with multipath effects and extensive Rayleigh fading. For mobile phone services these problems are tackled using:

- rooftop or hilltop positioning of base stations

- many base stations (a phone can typically see six at any given time)

- rapid handoff between base stations (roaming)

- extensive error correction and detection in the radio link

- sufficient operation of mobile phone in tunnels when supported by split cable antennas

- local repeaters inside complex vehicles or buildings

Other conditions may physically disrupt the connection surprisingly without prior notice:

- local failure when using the mobile phone in buildings of concrete with steel reinforcement

- temporal failure inside metal constructions as elevator cabins, trains, cars, ships

See also

- Anomalous propagation

- Field strength in free space

- Fresnel zone

- Knife-edge effect

- Multilateration

- Non-line-of-sight propagation

- Over-the-horizon radar

- Radio propagation

- Radial (radio)

- Real Time Locating

- Rician fading, stochastic model of line-of-sight propagation

References

- ^ Christopher Haslett, Essentials of radio wave propagation, Cambridge University Press, 2008 052187565X pages 119-120

- ^ Mean Radius of the Earth is ≈6.37 x 106 metres = 6370 km. See Earth radius

- ^ R.Busi: Technical Monograph3108-1967 High Altitude VHF and UHF Broadcasting Stations, European Broadcasting Union Brussels,1967

- ^ This analysis is for high altitude to sea level reception. In microwave radio link chains, both stations are high altitudes.

External links

|

|||||||||||||||||

- http://www.wireless-center.net/Cisco-Wireless-Networking/728.html

- http://web.telia.com/~u85920178/data/pathlos.htm#bulges

- Article on the importance of Line Of Sight for UHF reception

- Attenuation Levels Through Roofs

- Approximating 2-Ray Model by using Binomial series by Matthew Bazajian

This article incorporates public domain material from the General Services Administration document "Federal Standard 1037C" (in support of MIL-STD-188).

|

||||||||||||||